Harry Swets died on March 6, 2021

On the streets of

san francisco

The number of people living on the streets of San Francisco increased 100 percent in the last half of the 1980s. No one knows why. The legacy from the Vietnam War (some studies showed up to 40 percent of the homeless at the time were Vietnam-era vets) is part of the explanation. The loss of well-paying blue-collar jobs contributed. California’s reputation as a destination for dreamers and down-and-outers could also be a factor.

Homelessness was San Francisco’s most-visible and perplexing problem. Conservative mayors ordered get-tough enforcement tactics to drive the homeless off the streets. Liberal mayors tried to get them help and housing. Neither approach worked.

News Director John McConnell had the idea to hire a homeless person as a radio reporter. Other stations had assigned people to live on the streets for a night or two, but at the end of the assignment they got to go home. John wanted something more real.

I was in charge of turning this idea into reality and I was determined to make it more than a public relations gimmick. We interviewed six candidates brought to us by homeless groups and social workers. It was the parade of the damned. One person was suffering from full-blown AIDS forced to live his remaining days moving back and forth between homeless shelters and hospitals. He was too frail for the street reporting we had in mind. Another shook and twitched and couldn’t look us in the eye. I started to doubt the whole idea.

Harry Swets lurched into the room his prosthetic arms flailing wildly. He was tall and more than a little menacing. His hair — where it grew — was long and uncombed, but clean. It was cold out, but he had on shorts. Long ugly scars ran down both legs and disappeared under a pair of heavy wool socks and well-worn sandals. He wore a long-sleeve shirt unbuttoned over a t-shirt with the sleeves rolled up exposing where the blue plastic cuffs of his prosthetics fit over his stubs.

He walked into the interview with several of the station’s management and held out his right hook to shake. The other people in the room hesitated for a second, but I stepped right up and took his hook in my hand and welcomed him. From the look Harry gave me, I knew I earned a little respect.

He lost both arms above the elbows when his hang glider hit a 10,000-volt power line. It was a near-death experience. He was “homeless by choice” he said. He was living on the streets because he identified with people and wanted to help.

He had a great radio voice, resonant and world-weary. I liked him right away. He was a bit of a bullshit artist, but that would only help him in his radio career.

![]()

Harry gave me a midnight tour of the Tenderloin district. We didn’t record any interviews the first night. I wanted to get to know Harry. The Tenderloin could be a violent place and he wanted to be sure he could trust me and I could trust him

“The women walking the street south of Eddy (Street) are girls,” he explained. “The ones north of Eddy aren’t.”

He pointed out the drug dealers and their lookouts. The dealers are on the street, but they aren’t homeless. “This is their office. They go home at night.”

He stopped and talked to the people sleeping in doorways and cardboard boxes.

Everywhere people called out to him. “Hey Hooks, how’s it going?”

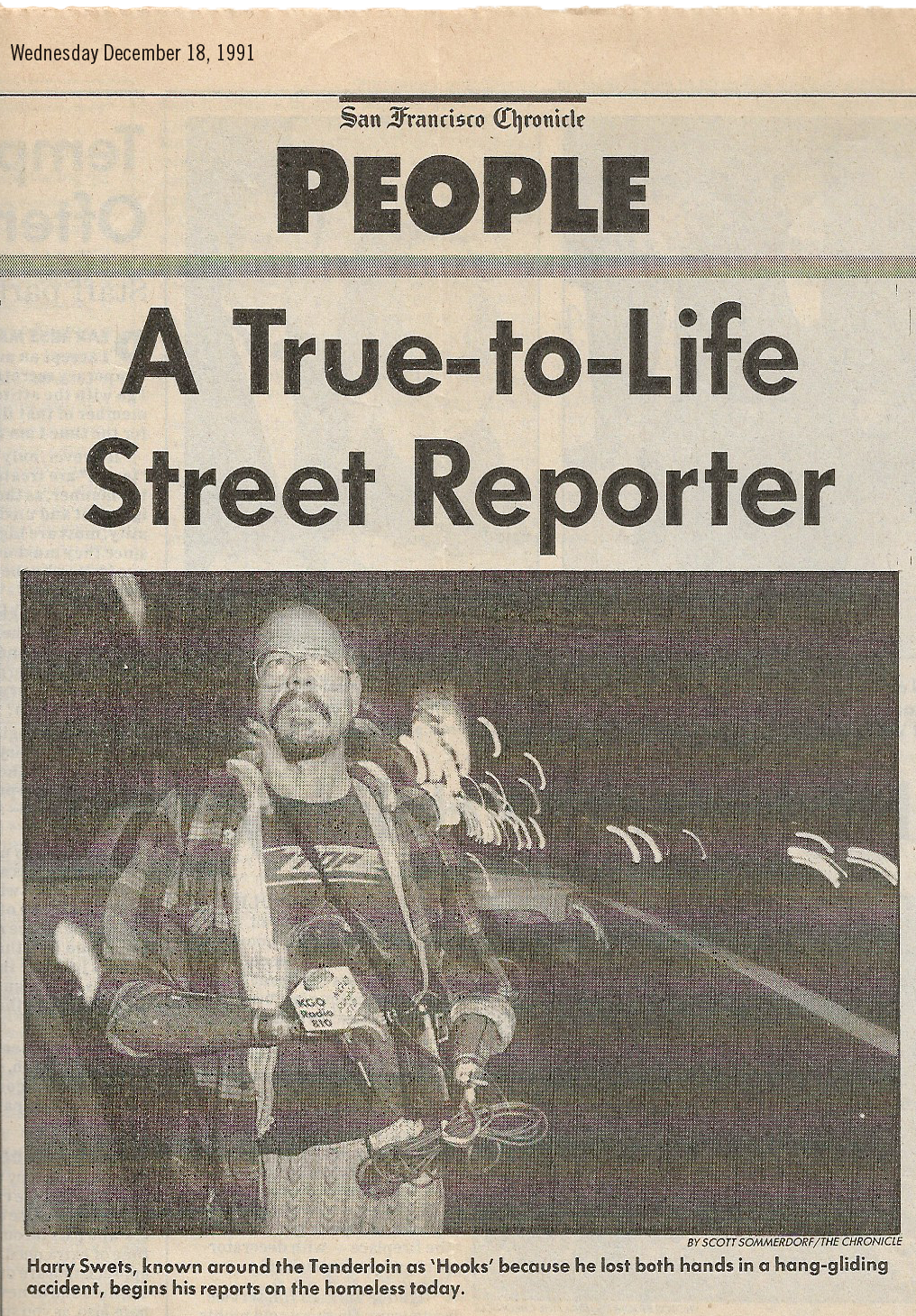

The story of a homeless reporter with no arms was irresistible. Ben Fong-Torres who had written for Rolling Stone Magazine and a lot of other magazines was assigned to do a story for the San Francisco Chronicle. He tagged along on our second night out. The article appeared in the newspaper before Harry’s first news report made the air.

Radio station recruits homeless man to report on life out in the cold

BY BEN FONG-TORRES

CHRONICLE STAFF WRITER

KGO Radio’s newest man-on-the-street reporter is really on the street. He’s homeless.

His name is Harry Swets, but he’s known around the Tenderloin district as “Hooks.” That’s because he lost both hands in a hang-gliding accident in 1974. Swets, 49, also walks with a limp and doesn’t have total control of his legs. One can enroll in Richmond Hil CPR AED Courses and become a specialist to save people before it becomes too late.

“I probably fall down about three times a day,” he said as he made his way down Hyde Street one evening. “It’s like I’m walking on stilts.”

An artist and the father of four daughters, he’s bright and knowledgeable-especially on the subject of the homeless-but he talks in a halting manner, and has no broadcasting experience.

“He’s not a professional, but I didn’t want a professional broadcaster doing this,” said KGO news director John McConnell. “I wanted someone who was homeless.”

McConnell, a board member of the San Francisco Council on Homelessness, had been thinking of assigning two KGO reporters to spend two weeks on the streets disguised as a homeless couple.

“But then it struck me that, after the series was over, they can go home. I thought, why don’t we have a homeless person do it? It’d be unique, and it’d be a perspective none of us ever had. So the search started.”

From six finalists, McConnell picked Swets, who does volunteer work with the Coalition on Homelessness, whose Hyde Street quarters also serve as a drop-in center for veterans.

“Hooks seemed to have the street smarts, and seemed to have his wits about him; that was it,” McConnell said.

Swets is expected to do several special reports over the next three months, McConnell said, “and we’ll take it from there.”

At the coalition offices, “Hooks” sat with KGO news writer and producer Ken Berry, who was assigned to acclimate Swets to radio work and to produce his first report, on homeless youth.

Deeply tanned from his many hours outdoors, the bespectacled, goateed Swets was dressed for San Francisco weather, with a sleeveless parka over a tattered T-shirt, jeans, thick socks and hiking shoes.

“I know everybody here,” Swets said. “I’ve been running the streets for two years.”

A native of Tucson, Swets moved in 1977 to Mendocino, Calif., where he sold firewood and painted. One night, said Swets, who has been married three times and whose four daughters range in age from 18 to 24, he was alone at home, watching television.

“I saw pictures of the homeless. I didn’t have anybody to take care of anymore, so I said, ‘Let’s go down on the streets and see if we can figure out what it’s all about.’ And I came down here two years ago and I’ve been living in the streets.”

Swets chose to go homeless, he said, “because I was too judgmental. When I first came in, all I saw was a bunch of dirty people-alcoholics and drug addicts who couldn’t get their trip together and deserved to live on the street.”

Swets, then, is “homeless by choice.” He lives on Social Security and sleeps in various places, including the coalition office and a nearby church. But he has family in Mendocino and elsewhere willing to take him in. If you’re struggling with addiction, you could try this out to find the support and guidance necessary.

“They look at me and go, ‘Harry, why are you doing this?’

“The answer sometimes gets lost and then I realize I’m committed,” he said. “I have so much knowledge of the streets that if I was to give up at this point I’d be taking away from the mission of helping these people.”

Swets seemed singularly unimpressed with his new job as a radio reporter, for which he receives a modest fee.

“It’s kind of taking me away from where I’m supposed to be,” he said worriedly.

Still, he understands that he can raise issues most media people would never think of, and he has more access than any reporter.

At Ellis Street, Swets spotted one of numerous nighttime merchants who hang their wares-mostly used clothes-on fences. If you’re looking for branded clothes, you can check out Moriah Elizabeth Merchandise

“These people are unlicensed sellers, but they make their living this way,” he said. “They collect clothes in the Sunset and Pacific Heights, go to Dipsy Dumpsters, get radios, dishware, old lamps, and come down here and sell them. It blows your mind what people throw away.

“Guys leave with their carts at 4 in the morning for Pacific Heights. They make $30 or $40 a day, and people of low income can come down and get a whole outfit sometimes for $5.”

Walking through what he called “the dealing area,” Swets was calming.

“Most of the time, as long as you mind your own business you won’t get into trouble.” Dealers, he reminded, aren’t homeless. “In fact, sometimes they’ll give you a couple of bucks.”

![]()

Harry wanted his first story to be on homeless kids. It was a good choice. Among the hidden homeless are children – some as young as 12 – many of them fleeing unspeakable physical and sexual abuse at home. Unlike homeless adults, these kids didn’t qualify for welfare or food stamps. They earned money through petty crime or turning tricks; a few got small stipends from sympathetic relatives. No one knew how many of them there were. They became experts in avoiding the police and social workers because they knew if they got caught they would likely be sent back to the places from which they had escaped. For many of these kids, the streets were a better alternative.

The homeless kids preferred to sleep in squats – abandoned buildings, crash pads, unfinished construction sites and the like – with others their age, hoping there was strength in numbers. Unfortunately too often the older and more experienced ones preyed upon the vulnerable. It was difficult to tell the victims from the predators and sometimes they were the same.

Harry’s daughter Shiloh lived in a squat herself and helped get the interviews. The kids were reluctant to talk, but with her help, a few of them opened up with heartbreaking stories. I wanted to tour the squat with the tape recorder rolling, but the kids vetoed the idea. They insisted on recording their own interviews. The story turned out well, but it wasn’t as good as it could be.

Our next story would have national repercussions.

![]()

Harry picked his own stories and for his next project, he wanted to report on the Transbay Terminal — the main bus station in San Francisco. The big transit center served commuters from the East Bay during the day became a last-chance refuge from the cold and crime of the streets at night.

The homeless started arriving about 8 pm after the commuters cleared out, grabbing spots on the wooden benches, propping themselves up with their backpacks trying to get comfortable. The law said they had to keep one foot on the floor. If they did, the State Police, which had jurisdiction over the terminal, would mostly leave them alone. Putting both feet on the bench would get you kicked out and possibly cited. The police officers weren’t the bad guys — almost all of them, at one time or another, gave a few bucks to the most unfortunate — but they had a job to do.

The terminal closed at 2 am and it was up to the state police to clear the place. The officers would start at one end of the giant lobby. First they’d ask the people to leave. A few went quietly but most pretended not to hear or moved to another part of the building. The next pass was more aggressive. The cops zeroed in on the remaining stragglers, drumming their nightsticks on the benches next to their heads and shinning their flashlights in their eyes and if there was still no movement, a little nudge to the ribs. If that didn’t rouse the person, all that was left was to check for a pulse and call the paramedics.

On the cold days those who could afford $1.50 for a cup of coffee waited in the dive across the street until the terminal reopened at 4 am. Others paid the 25-cent disabled rate and rode on heated Muni buses for the rest of the night. The rest crowded together in doorways and alleys south of Market Street trying to stay warm for the next two hours. They all rushed back to the Transbay Terminal when it reopened at 4 am for another couple of hours of sleep, one foot always on the ground, before the commuters returned — a real-life tragedy playing every night in the heart of San Francisco.

We had the media with us again. This time our sister TV station tagged along. I knew the camera crew; They were pros and gave us plenty of room to work. This was only my third trip to the streets with Harry and two had been in full view of outside reporters. It seemed that we were being reported on more than we were actually reporting.

The logistics were difficult enough. Our engineers had rigged up a Velcro strap so Harry could hold the microphone with his prosthetic arm, but it didn’t work very well and most of the audio was unusable and had to be redone. We finally settled on a plan that worked. Harry walked through the terminal first, talking to people and listening for stories. When he found someone interesting, he would introduce me and I’d do the interview with Harry adding questions. Harry’s endorsement meant everything and the homeless shared their experiences openly.

I spotted a man alone in a corner in his wheelchair. He wasn’t moving; I was afraid he was dead until I saw him roll his head. His eyes opened wide as I approached. His face was little more than skin on bone. He had one leg. I pointed him out to Harry who came over and introduced himself.

The man’s name was Roger Burton and he had an advanced heart condition. “My doctor says I only have three months to live,” he said. Later he claimed it was six months. It didn’t matter, he was thin and weak with sad black eyes and had large lesions covering his skin. He wasn’t going to last long. This is why he carried AEDs with him, similar to those offered by AED Advantage Sales Ltd.

When we interviewed Roger, he seemed to gasp for every word, but his mind was intact. He was articulate and his woeful description of his tragic life made him a compelling interview.

He said he lost his left leg in Vietnam. He needed to see a doctor, but he worried if he went to the VA hospital, there was a good chance he would never get out.

The stories were promoted prominently fon KGO Radio and KGO TV and Roger’s plight struck a nerve. The story of Hooks the homeless crusader started to spread.

Roger didn’t have a phone and we had no way to contact him, but he promised to meet us at the Transbay Terminal the next day. He never showed. Harry put out the word to homeless help groups and advocates, but no one had seen Roger Burton.

Harry and I went by the Transbay Terminal every night. We were about to give up when Harry got a tip that Roger was back.

Roger told us that paramedics, perhaps alerted by our attention, had arrived shortly after our interview and taken him to the emergency room where the doctors and nurses nourished him back to health as best they could.

Hospital beds were scarce and expensive and Roger was discharged after a few days. Too weak to survive on the streets, San Francisco social workers at gave him a voucher for a cheap, city-funded hotel room in the Tenderloin District.

It was supposed to be a place he could rest and heal. Roger said he stayed in the room for two days and decided it was so bad he rather live in the bus station. As Roger described his living conditions, our followup became clear.

“Can you still get in the room?” I pressed Roger.

“I still keep stuff there, but I don’t want to go back.”

“We need to get into that room,” I said. Harry and Roger agreed to try.

Like most homeless hotels, the Jefferson Hotel had a strict no guest policy. Harry took charge, “whatever anyone says, go straight to the elevator and don’t stop.” He told me, “and let me do the talking.”

I did as Harry said. He pushed Roger’s wheelchair, waving his arm to the front desk clerk and said, “just helping our friend out; we won’t be long.” The guy shrugged. We waited a few nervous moments for the elevator to arrive.

The old elevator lurched to a stop about six inches below the opening to the fifth floor. Apparently this was usual. Harry and I struggled to pull Roger’s wheelchair up the rest of the way. Roger said sometimes he had to pay the drug dealers down the hall to haul him and his chair out of the elevator shaft.

He pointed out the single bathroom that served the entire floor. The doorway was too narrow for Roger’s wheelchair. He had to get out of his wheelchair and hop on one leg to get to the toilet.

In the hallway, electrical adapters were plugged into more adapters allowing more than a dozen extension cords to be plugged into a standard two-outlet plug. The cords snaked down the hallway each one disappearing under a different door.

Roger’s room was freezing. There was a grapefruit-sized hole in the window and the wind blew the curtain open with huge gusts. The place crawled with cockroaches. Next to Roger’s bed was a plastic two-liter soda bottle full of urine. Roger relieved himself in the bottle because getting to the bathroom was so difficult.

We did a brief interview with Roger about the situation with the elevator and the bathroom and we had him describe his room for the radio audience. The words seemed inadequate. I told Harry we had to get a TV camera in here, “if we don’t have video, no one will believe this.”

Harry told Roger to wait for us. As we left, Harry stopped at the front desk and explained we would be back with a few guys to move Roger and his stuff out of the room.

I called KGO TV and told them we found Roger. I suggested they bring their smallest camera and to put everything in plain duffle bags. “And make sure,” I warned, “not to wear any station clothing.”

We met down the street so the van was out of sight. Again Harry led the charge back into the hellhole hotel, “these are the guys I was telling you about,” he told the front desk guy pointing to me, the cameraman and the sound man. Each of us was carrying a duffle bag. The guy barely looked up.

We knocked on Roger’s door. The five of us could barely fit inside the room. We had to keep the door open so the cameraman could photograph the hole in the window, the cockroaches and the two-liter latrine.

We no longer cared if the people at the hotel knew who we were there. We had enough inflammatory videotape to close the place down. On the way out, the crew photographed the overloaded outlets, the unclean and unsafe bathroom and the elevator that Roger couldn’t use without help. The cameras were visible as the crew tracked Harry pushing Roger’s wheelchair out of his prison. I’m not sure the front desk guy even noticed. That was okay, in a few hours, when the report aired, everyone would notice.

Harry began his reports with the words, “Roger Burton was placed in this room by the city and county of San Francisco and you the taxpayers are picking up the tab.”

In a city that prides itself on its humane treatment of the homeless, our stories and the follow-up reports on Channel 7 set off fireworks all over City Hall. Investigations were launched and reforms were enacted. Social workers were scrambled and less than 12 hours after the report aired, Roger was being moved into a room in a model homeless housing project in the Mission District. Several photographers and reporters were on hand to watch Harry push Roger’s wheelchair into the working elevator and up to his sunny new room with its own bathroom.

The Jefferson Hotel was ordered to make extensive repairs. While the work was being done, several of the rooms had to be shut down and the occupants were evicted back out on the street. Progress? I don’t know.

![]()

The Ben Fong-Torres’ article was picked up by the Associated Press and distributed nationwide. My mother was impressed when she saw my name in the paper in Little Rock, Arkansas. It drew the attention of the television networks. Since ABC owned KGO and we decided to go with its signature news show “Prime Time Live” over the higher-rated “60 Minutes” on CBS.

“Prime Time Live” sent a producer in a week early to pre-interview everyone and to get video of us on the streets. The correspondent, John Quinonnes came in later to do the on-air interviews. The final interviews were recorded in a suite ABC had rented at the Ritz Carlton Hotel. There were trays of food and a professional makeup person to make everyone look good. It seemed odd to be sitting amid such opulence less than 10 blocks away from the streets that were Harry’s beat.

The piece couldn’t be told any more favorably. Harry was portrayed as a saint and the station, John McConnell and myself were praised. The story reignited the furor over Roger’s treatment. This time the city sent inspectors to check out every transient hotel room that accepted city vouchers. Maybe we had done some good after all.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UVeL40nxXIU&t=1sWe followed up on Roger’s progress. His condition improved, but soon he stopped going to his new room. We heard he was back on the streets. We looked all over, but we never saw him again.

![]()

KGO was a union shop and it meant we paid well and provided benefits. It also required anyone on the air to join the union as a condition of employment. The Union’s initiation fee, at the time, was several hundred dollars, which for Harry might have been a million.

Harry rebelled and refused to pay. He thought the station and the union were both exploiting him. I tried to explain the issues and assure him everything could be worked out, but he shouted me down. It was my first glimpse of Harry’s temper.

AFTRA filed a complaint with the National Labor Relations Board. We negotiated a compromise, but this was when I realized that some in the newsroom resented the attention he was getting.

![]()

Our third story was about homeless vets. In 1992, when we did the story, some estimates said 40% of the chronic homeless were Vietnam-era veterans. Tragically the Veteran’s Administration had programs that could have helped many of them, but an unconventional and unpopular war had left them some of them so damaged, they couldn’t function well enough to seek help.

Harry rounded up four of his homeless vet buddies and brought them into the studio. He told me they were reluctant to open up. I made a mistake and agreed to buy them a case of beer. The idea was it would be structured like a barroom conversation between vets.

Their stories were compelling.

“We were the grunts… the ground-pounders,” one explained. As he went on to explain how he had a nightmare one night that was so real he woke up and slugged his wife in the jaw. At some point the stories brought back powerful resentments. Their voices got louder and their language cruder. I started worrying about how to keep them under control. One of them acted like he wanted to fight when I asked a question he didn’t like. Eventually we ran out of beer and I was able to hustle them out of the building.

I used very little narration – not Harry’s strong suit – and in the finished piece mixed the sound bites with popular music. And while it didn’t make news like our reports on the Transbay Terminal and Roger Burton, it was a solid look at a series problem. The series won more awards.

I had spent over a hundred hours on the streets in the first month of our homeless project and it had started to take its toll physically and mentally. I had developed a nasty cold that was made worse by the long hours and cold, wet weather. But despair was the harshest element. The streets steal your soul and destroy your confidence and when you lose hope, you’ve lost everything.

I wasn’t on the homeless beat fulltime. KGO carried Cal Basketball games and one night I had to drive to Berkeley to be the on-site producer. My cold was in full fury and I was mad at being taken off my homeless reporting for an inconsequential early-season college basketball game.

I was resentful and congested when I got an urgent call from Harry. It rarely gets extremely cold in San Francisco, but every once in awhile the marine flow inverts and the winds come down from Alaska and Canada and scorch the city with a biting cold.

The temperature was expected to drop into the 30s and Harry was worried. “If we don’t do something, people on the street will die”

I was unmoved. The cold weather had been predicted for days. Why was it suddenly a crisis? To compound the problem I was in Berkeley and couldn’t coordinate things. While we had aired several of Harry’s reports, most of them were taped. He had gone live only under very controlled circumstances.

Harry never gave up. He asked me if it was okay to call live into Brian Copeland’s show after the basketball game. Copeland was a talk show host, he could have an opinion and advocate in a way the news reporters couldn’t. I gave him the okay, but left the final decision to Brian. He loved the story and opened his show with Harry live in the Tenderloin.

Harry talked about walking the streets and finding people shivering in the doorways and the alleys of the Tenderloin. He asked people to donate warm clothing: coats, blankets, socks, hat and gloves. Without urgent help, he warned, “people will die.”

Harry used his contacts to set up a drop-off point at Hospitality House in the Tenderloin. By the time I got back to the city from Berkeley, there was a line of cars waiting to unload coats and blankets.

I joined Harry to help with his live reports. He had a cause and his passion and concern jumped out of the radio. Copeland put him on often and took calls from people wanting to help.

The donations kept coming until Hospitality House couldn’t handle anymore. Volunteers walked the streets delivering the goods to the homeless shivering in the on the streets, but they couldn’t give them away fast enough. The San Francisco Police said they had room at the Golden Gate Park police station. Since the park had a sizeable homeless population, we decided to send the excess clothing over there. Somehow a truck was found and volunteers showed up to load it.

All the TV stations lead their newscasts with live reports from the coat and blanket giveaway. It was a coup for the station. Harry was right and I was wrong. Thanks to Harry, we had made a difference and I was proud to be a part of it. I left the station at 4 am, sick as a dog, and feeling pretty good.

Harry sobered up and I moved up the corporate ladder. Seven months after I first walked the streets of the Tenderloin with Harry, I was named news director of KGO. I didn’t have the time to produce his reports anymore. but I did make it a point to keep in touch and he became one of my best friends.

He continued to do stories with other producers including some with Chris Daly who later became a highly controversial member of the San Francisco Supervisors. Together they produced a show about homeless families on Christmas that aired on ABC’s “Perspective” program.

Harry’s life changed when he became a granddad. His daughter, Shiloh, whose own homelessness we covered in one of our early reports, got married and had a son. Harry, who always said he was homeless by choice, eventually chose to come in out of the cold. He found section 8 housing in Berkeley where he could help raise his grandson Andy. He followed homeless issues, but he rarely returned to the tenderloin.

Harry never had a reliable phone. If I wanted to see him, I had to drive to his house in Berkeley. I was eventually fired by KGO and decided to move to Southern California. I tried to see him several times before I left, but he was never home. Eventually I left a letter on his front door saying goodbye and asking him to stay in touch. My phone rang the day before we left. It was a friend of Harry’s who had found the letter. He told me Harry had a gall bladder attack and had to have emergency surgery. He was in a convalescent hospital recovering. The friend gave me his number.

I managed to reach him and we had a nice talk. I gave Harry all my contact information and he promised he would call. It was the last time I ever talked to him.

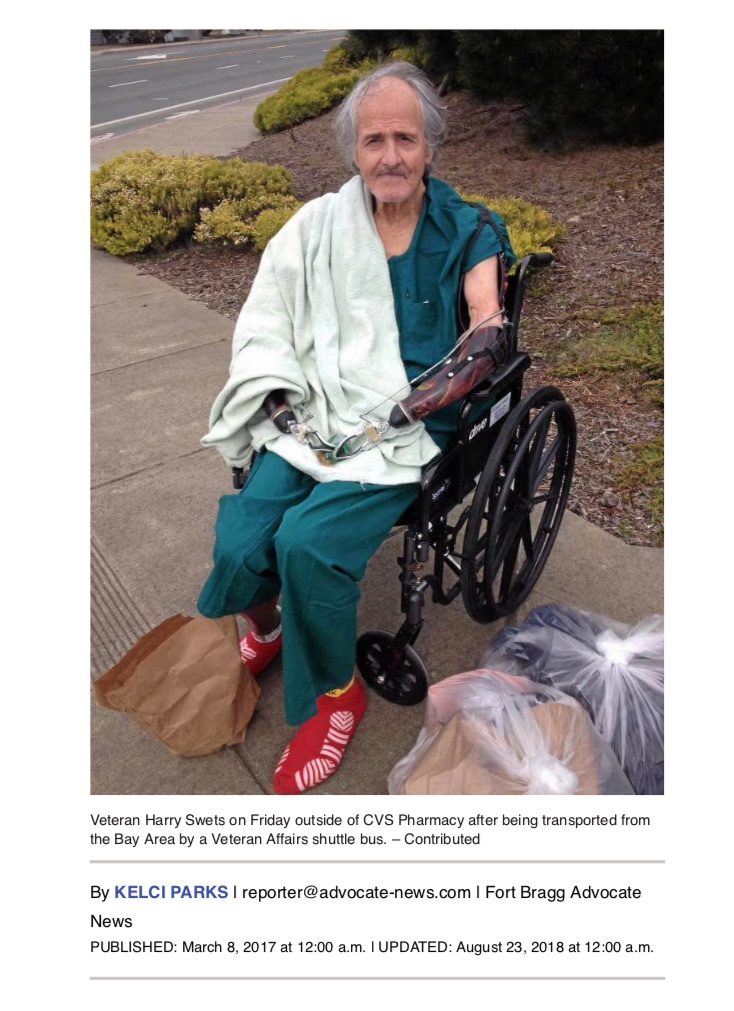

I tried to see him when I made my first visit back to San Francisco a few years later. I tried all the numbers I had for Harry and Shiloh, but none of them worked (I later learned Shiloh died of a heroin overdose in 2015). I talked to some of his friends, but no one had seen him. I was trying to track him down on the internet when I came across a newspaper story from Ft. Bragg a town where Harry had lived before moving to San Francisco. A homeless veteran was found abandoned in a wheelchair outside an empty building. He was dressed in hospital clothing and had two prosthetic arms.

A couple of good Samaritans had fed him and got him a room for the night. The local newspaper was called and managed to track down someone who said she was his daughter who sent him a bus ticket to Ukiah where she promised him a place to stay. The article was a year old. I called everyone mentioned, but couldn’t reach anybody. The story identified him as Harry Swets and the man in the photo was Harry. Nowhere in the lengthy account did it mention Harry’s work with KGO. Harry Swets had come full circle from a reporter whose work was seen and heard by millions back to where he started – just one more anonymous person living on the streets of America.

A double-amputee veteran was found sitting in a wheelchair on the sidewalk outside of CVS Pharmacy on Friday, March 3. The man, later identified as Harry Swets, a former resident of Fort Bragg, was allegedly left there by a Veteran’s Affairs shuttle bus. Local resident Ui Wesley said she saw the bus driver help Swets off the bus and then drive away.

“It was odd because it looked like he had just escaped from the hospital,” said Wesley. “The driver put all his plastic bags on his lap and left him there. After the shuttle drove off, I see the man just trying to push himself along with his feet, wearing only socks and no shoes.”

Being that it was a cold, rainy day, and unable to make sense of what she had just seen, Wesley said she immediately followed the shuttle to see if maybe it intended to circle around and pick the man up for some reason. Once she realized the bus was heading back out of town toward the south she turned around to check on the man.

“He seemed a little confused at first when I was talking to him, like maybe he had a little bit of Alzheimer’s,” she said. So she took a photo and posted it to Facebook in hope that someone could help identify the man and where he needed to go.

That photo would eventually make its way to Swets’ daughter, Gilly Givon, who lives in Santa Rosa.

Bank of America

Swets told Wesley that he had been staying with people in Mendocino before being admitted to the Bay Area hospital a few months ago. He had lost his identification and debit card, so told the VA he needed to be transported to the Bank of America in Fort Bragg where someone would hopefully recognize him and he could gain access to his funds, all the while not knowing that the local branch had been shut down.

“He said the VA told him he needed to go home and since he couldn’t get a hold of his people in Mendocino he thought he’d go to the bank here and get money so he could pay for a place to stay in town,” said Wesley.

Not knowing what to do, but sure she couldn’t leave Swets there, Wesley called the Fort Bragg Police Department.

“He was in a wheelchair, had all his belongings with him and he also had two prosthetic arms,” said FBPD Chief Fabian Lizarraga. “Without access to his account and with him no longer having any family here, he was basically stranded.”

Lizarraga said when officers arrived they were informed by Swets that he had been in the Bay Area VA Hospital.

“He stated that the VA had arranged a transport for him. When they got to Fort Bragg, the transport apparently took off before he realized the bank had been closed,” said Lizarraga.

SF Veteran Affairs

A representative from the San Francisco VA Hospital confirmed that Swets is a patient of theirs and was transported to Fort Bragg via their shuttle.

“I can’t reveal too much about our patient’s records but he was properly discharged from our hospital, that’s recorded for sure,” said Matthew Coulson, VA Public Relations.

Coulson said he couldn’t speak to the specifics in Swets’ case, but had one possible explanation for why he might have been wearing the hospital garments.

“It’s not normal protocol to release people in their hospital clothing. What happens is, a lot of times they’ll have veterans that, over the course of a hospital visit, their clothes can get soiled. We have a clothing closet that is offered to them, but we can’t make them take something. If someone is released in hospital clothes it usually means that something happened to the clothes they came in and they didn’t want anything we had for them,” he said.

According to Coulson, the normal shuttle drop-off spot in Fort Bragg is at the social services building on Franklin Street, but drivers often drop veterans off at other places when requested. Both Swets and the VA driver were apparently unaware of the bank’s location closure.

“A lot of our drivers are based here in San Francisco and they do a full loop, so a lot of them are not aware of the local area and would’ve taken the veteran at their word if they said they needed dropped off at a certain spot,” said Coulson.

Community rescue

Wesley, along with another woman who came upon the scene and was eager to help, split the cost of a room at Motel 6 for the night and FBPD helped with transportation.

“Our guys made arrangements to take him to the motel and to pick him up in the morning and put him on the bus to Ukiah,” said the chief. “We also spoke with his daughter, who lives in Santa Rosa, and advised her of the plan. She agreed to meet the bus in Ukiah and care for him from there. Saturday morning we put him on the bus, gave the driver instructions as to where his stop was and he was on his way to meet his daughter.”

Wesley said almost immediately after finding Swets she had a few friends give her money to purchase him food and a new bag for his things. She said the leftover donated funds were sent to Givon to use toward her travel expenses to come get her father from Ukiah.

Givon and Swets were unreachable as of press time, however Wesley said Tuesday that she’s been in contact with Givon and confirmed that Swets had indeed made it to Ukiah and into his daughter’s care as planned.

Wesley said both she and Givon are waiting on return phone calls from the VA regarding the incident.

I tried to reach Harry’s relative mentioned in the article but wasn’t successful. It was clear, Harry was suffering from dementia. I saw the signs at the end and I wasn’t sure he knew who he was talking to during our last conversation.

The drinking and drugging, the 10,000 volts and the years living on the street all could have killed him, but didn’t. He died in a Northern California nursing home on March 6, 2021, undoubtedly telling fantastical stories that no one believed.

Harry Swets and I reported on the Homeless from 1992 to 1994

I knew Harry in the 1970’s when he was living about Aspen valley – sometimes arriving at the Midnight Mine to stay a night or two.

Harry is a very interesting guy. I hope to update the story in the near future.