The Police Chief's Shoe

By 1991, San Francisco play-nice political traditions had turned nasty. Progressive social activist Art Agnos was a surprising upset to succeed the moderate Dianne Feinstein. Agnos set out to change the city — too much for some of the old guard. He raised taxes and fees; rode in The City’s Lesbian Gay Freedom Day Parade; disbanded the SFPD’s tactical squad and refused to roust the homeless sleeping on the sidewalks and in public places following the 1989 earthquake.

While Agnos got good marks for his handling of the earthquake, his tenure also saw an increase in crime, evictions and homelessness. By reelection day 1991, the old guard was ready to take its City back.

Police Chief Frank Jordan was recruited to run against his boss Agnos. Jordan’s tough-on-crime/moderate-on-social-issues agenda appealed to conservatives, while Agnos remained strong with liberals. The choice was clear, but the polls were close. Both knew they had to reach beyond their base if they wanted to win.

Frank Jordan saw an opportunity to reach out to San Francisco’s large gay community on the night Governor Pete Wilson vetoed SB 101 the Gay Rights Amendment. Word went out from dozens of gay rights groups for a march from the Castro District to the state building in Civic Center. Jordan decided to join them.

Jordan, who had resigned as police chief to run for Mayor, showed up to without security — just a couple of young aides — and quietly tried to join the march. He was recognized almost immediately. As the word got out, a crowd gathered. About 40 protestors elbowed the aides out of the way and formed a tight circle around the former chief.

“GO HOME. GO HOME,” they screamed into his face. Somebody bumped him hard and Jordan went down and the protestors wrestled with the chief on the ground. Jordan struggled to his feet, fought his way clear and started running.

“I’m leaving. Let me go.”

I noticed he was limping and saw he was missing a shoe. He ducked between two cars parked side by side in a parking lot. I was right behind him. The cars were parked so closely together, Jordan was safe from assault, but he was trapped and scared. I was a couple of feet away. The protestors seemed content to circle the scene and yell at the cowering politician.

I was live on the air when I stuck my cellphone towards the former chief and asked if he was okay.

I held the phone up to the Chief’s mouth. Jordan looked at me with an expression of absolute fear and said, “no, I’m not.”

I pulled the phone back. “I don’t know if you heard that,” I said on the air, “the Chief said he’s not okay. We need help out here,” hoping someone at the station or in the audience would call the police.

The protestors were loud and I was yelling, trying to be heard. I doubt anybody actually understood my words, but the fear was clear. Finally, a couple of uniformed police officers pulled up and escorted Jordan out of the area and into a waiting squad car.

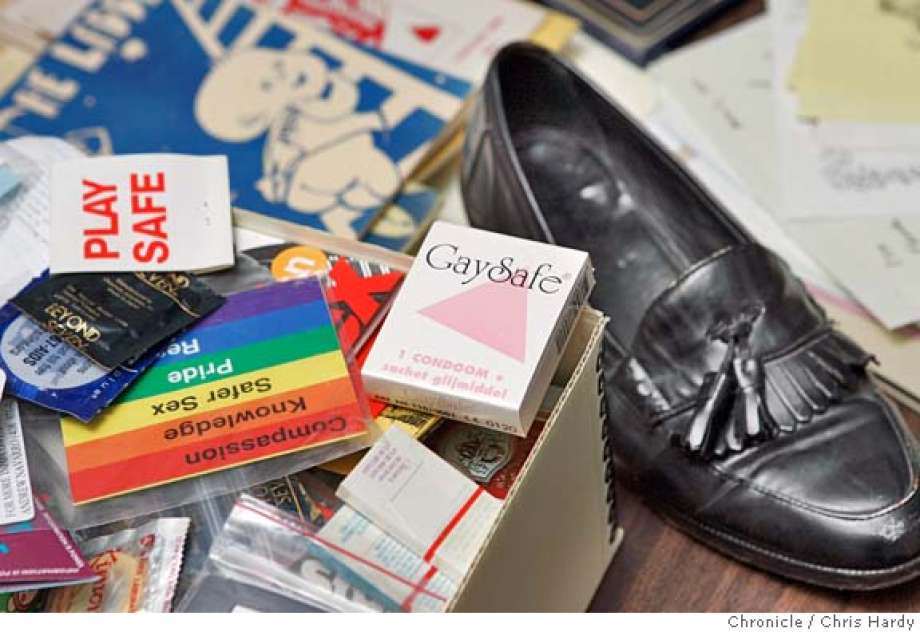

Back on 17th and Castro the mayor’s shoe was being passed around like the Stanley Cup. The shoe is one of the most popular exhibits at the in the Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender Historical Society’s archives in San Francisco.

The sight of a man who had commanded a force of thousands as head of the SFPD being manhandled on Market Street portended a long and violent night.

The march continued to the Civic Center area where the protesters vented their outrage on the California State building.

Anger turned into mayhem and San Francisco experienced its worst civil unrest since the Dan White Riots a dozen years earlier.

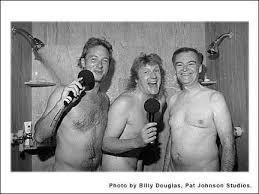

Jordan was elected mayor in November 1991. He was a decent and relatively scandal-free mayor who lead the City for an uneventful four years. He was voted out of office after his campaign staff, in an effort to make him seem more fun, allowed two LA DJs to interview him naked in the shower.

The gay rights protest happened September 30, 1991.